_case study

_institutional

_institutional

A Museum for Sculpture

“Sculpture records the first naive, unperplexed recognition of man by himself”.

- Walter Horatio Pater,

Playing on the contested space between the body and architecture, the thesis explored how the relationship between form and figure could be manipulated to create a novel approach to design.

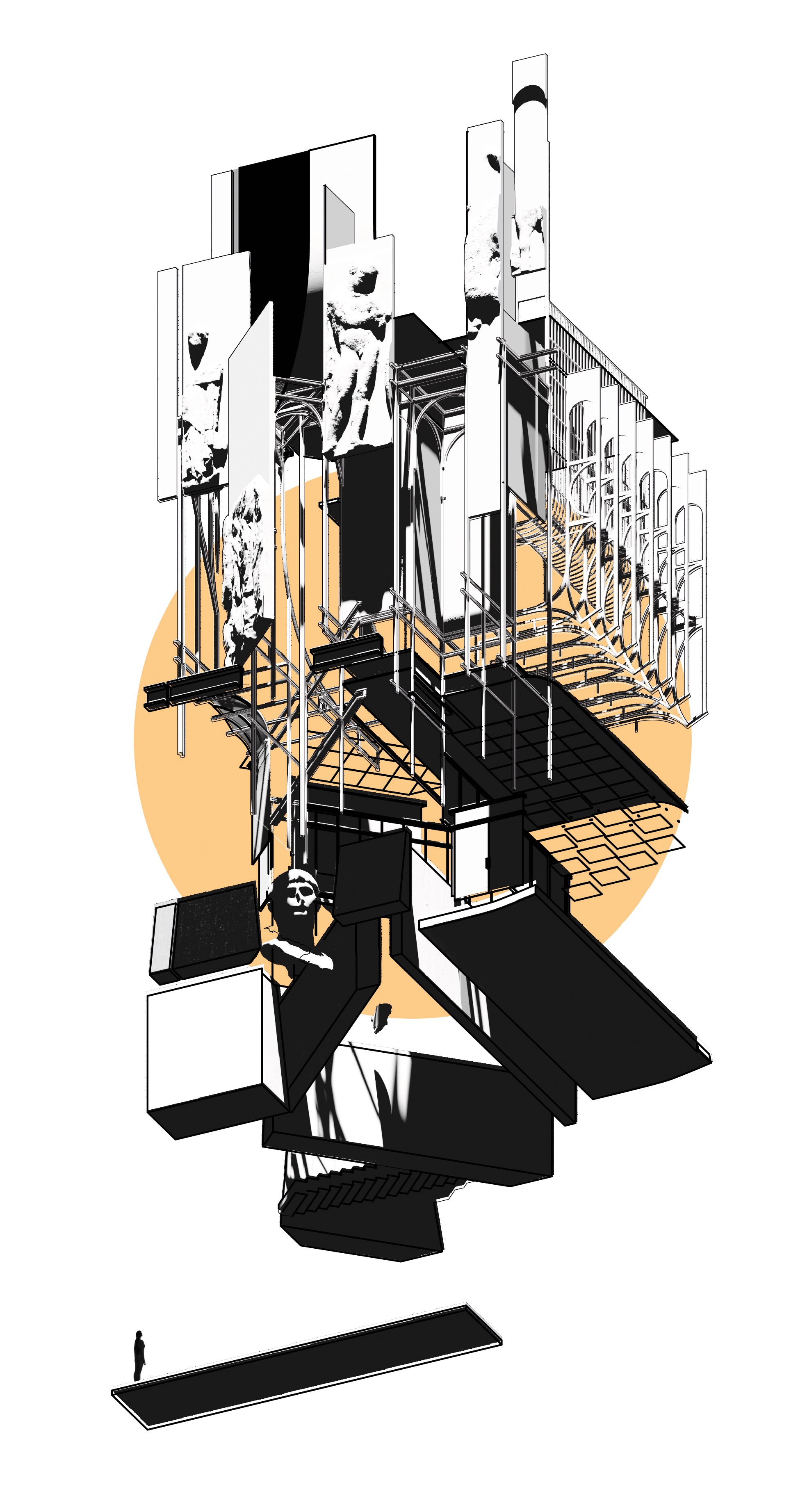

Proposing the ‘Museum for Staging the Figure’ as an extension to the British Museum, the design considered new technologies of replication and serialization to question the existing museum, and how architecture can integrate the historic object in the city.

Architecture emerges in the form of the pedestal, the original construct that mediates figure and setting. Just as the pedestal allows for the duplication of the body into architecture, the manipulation of the interaction between the Museum and its inanimate inhabitants blurs the line between the subject and object of the setting. This allows for an architecture to emerge out of a bodily empathy to the material frame, distinctly sensational in its muted narrative.

The serial nature of capitols, column, doors, handles, allow us to deal with form that would be sculptural where it not for their commonplace nature that drapes something of a non-existence about them – each one of their ‘form’ becomes subsumed by being representational of all others like it, suffering the effects of mass production and commodification in a different way than other individual forms do. This serialization makes forms into figures – purely representational devices. I apply a similar thinking to both building and sculpture.

Summary

The thesis’ exploration of part-to-the-whole begins with the limbs of ancient figure-sculpture that emerged from the ground in 15th century Rome. Uncovered, they demanded a spatial setting novel to architecture. The act of accommodating the fragmentary body parts of statues necessitated the creation of various new types, like the gallery, the niche, and the circular exhibit room. Tracing early Museum case-studies, the thesis centers itself on Michelangelo Simonetti’s 18th century re-design of the Vatican Museum, understood in conjunction with a ‘haptic’ way of seeing and the neo-classical fragment.

Importantly, classical sculpture is arguably a very early example where we find serialization of sculptural types, for example in ancient Rome and Greece. Here

statues existed at times as hundreds of copies with no clear original. At other times, copies were mass-produced based on verbal descriptions, simulacra of a piece that may or may not have existed.

The ability to use architectural types as series creates ‘representational space’ – a plane at which form looses its specificity, just as what is commonly referred to as ‘sculptural architecture’ is then an abstraction of already established architectural form.

Pedestals originated with the need to show a form, most often human. The pedestal implies the object as much as it does the subject (and where they stand), thereby navigating the transition from ground to figure.

in the setting of this project the Pedestal has more so than any other archetype been useful as a symbol for architecture; a form that mediates between the material transitions that make art – from idea to material, or in terms of figure sculpture, from flesh to stone.

Importantly, classical sculpture is arguably a very early example where we find serialization of sculptural types, for example in ancient Rome and Greece. Here

statues existed at times as hundreds of copies with no clear original. At other times, copies were mass-produced based on verbal descriptions, simulacra of a piece that may or may not have existed.

The ability to use architectural types as series creates ‘representational space’ – a plane at which form looses its specificity, just as what is commonly referred to as ‘sculptural architecture’ is then an abstraction of already established architectural form.

Pedestals originated with the need to show a form, most often human. The pedestal implies the object as much as it does the subject (and where they stand), thereby navigating the transition from ground to figure.

in the setting of this project the Pedestal has more so than any other archetype been useful as a symbol for architecture; a form that mediates between the material transitions that make art – from idea to material, or in terms of figure sculpture, from flesh to stone.

While the plan is instrumental in arranging a seamless order, it is a project designed in section and perspective, focusing on transitions between differences rather than alignment. The ground is formed to serve as the only true ‘boundary’, both vertically and horizontally.

The early concept model began with wanting a conversation about the role of foundations as plinths, where both the visitor and figure sculpture equally commit a series of stereotomic operations to create a place for themselves, whether it is by demands of light, circulation or a confrontation. The more generic parts of the building are then draped above it.

A key drive of the project was the suggestion that reproduction provides an opportunity to play on the expectation of scale, and that fragmentation created the necessity of the visitor to begin to relate to these mutilated fragments. As much as navigating the building, the visitor would have to orientate themselves among changing perceptions of their own scale and make-up, and the architecture set itself secondary to that relationship.

This was allowed by the British Museum, just the same year (and just before covid) uploading a free library of detailed 3d scans of their collection.

Ultimately, the building reveals itself not to be a museum, but a device that allows for the production of experiences that prime and insinuate the subjective singularity of the confrontation with the abstracted body. Mirroring the British Museum, it re-maps the existing exhibits with new expectations of the tension between figure and its setting, re-asserting an awareness of the visible plane as the play between expressive, articulated surfaces. Defeating the singularity of any one figure, it never-the-less asserts the autonomy of separate moments where the body demands a setting, accumulating these into a conception of the building as a interactive whole.

A central feature of the British museum are the 'Elgin marbles', or rather the Parthenon frieze - one of many contentious acquisitions by the museum. In the original museum, there is a room that reads like a bad architectural joke, the marbles set facing inwards in a room decorated with Doric columns.

Though not strictly a façade, they were originally outwards facing. So, to continue the play on architectural ambiguity between sculpture and architecture that a frieze embodies so well, the façade of the proposed museum sets magnified reproductions atop a very literal plinth.

Though not strictly a façade, they were originally outwards facing. So, to continue the play on architectural ambiguity between sculpture and architecture that a frieze embodies so well, the façade of the proposed museum sets magnified reproductions atop a very literal plinth.